- Home

- Quizzes

- My Quiz Activity

- Newsletters

- Sports Betting

- MY FAVORITES

- Add Sports/Teams

- SPORTS

-

NFL

- NFL Home

- Arizona Cardinals

- Atlanta Falcons

- Baltimore Ravens

- Buffalo Bills

- Carolina Panthers

- Chicago Bears

- Cincinnati Bengals

- Cleveland Browns

- Dallas Cowboys

- Denver Broncos

- Detroit Lions

- Green Bay Packers

- Houston Texans

- Indianapolis Colts

- Jacksonville Jaguars

- Kansas City Chiefs

- Las Vegas Raiders

- Los Angeles Chargers

- Los Angeles Rams

- Miami Dolphins

- Minnesota Vikings

- New England Patriots

- New Orleans Saints

- New York Jets

- New York Giants

- Philadelphia Eagles

- Pittsburgh Steelers

- San Francisco 49ers

- Seattle Seahawks

- Tampa Bay Buccaneers

- Tennessee Titans

- Washington Commanders

-

MLB

- MLB Home

- Arizona Diamondbacks

- Atlanta Braves

- Baltimore Orioles

- Boston Red Sox

- Chicago White Sox

- Chicago Cubs

- Cincinnati Reds

- Cleveland Guardians

- Colorado Rockies

- Detroit Tigers

- Houston Astros

- Kansas City Royals

- Los Angeles Angels

- Los Angeles Dodgers

- Miami Marlins

- Milwaukee Brewers

- Minnesota Twins

- New York Yankees

- New York Mets

- Oakland Athletics

- Philadelphia Phillies

- Pittsburgh Pirates

- San Diego Padres

- San Francisco Giants

- Seattle Mariners

- St. Louis Cardinals

- Tampa Bay Rays

- Texas Rangers

- Toronto Blue Jays

- Washington Nationals

-

NBA

- NBA Home

- Atlanta Hawks

- Boston Celtics

- Brooklyn Nets

- Charlotte Hornets

- Chicago Bulls

- Cleveland Cavaliers

- Dallas Mavericks

- Denver Nuggets

- Detroit Pistons

- Golden State Warriors

- Houston Rockets

- Indiana Pacers

- Los Angeles Clippers

- Los Angeles Lakers

- Memphis Grizzlies

- Miami Heat

- Milwaukee Bucks

- Minnesota Timberwolves

- New Orleans Pelicans

- New York Knicks

- Oklahoma City Thunder

- Orlando Magic

- Philadelphia 76ers

- Phoenix Suns

- Portland Trail Blazers

- Sacramento Kings

- San Antonio Spurs

- Toronto Raptors

- Utah Jazz

- Washington Wizards

-

NHL

- NHL Home

- Anaheim Ducks

- Arizona Coyotes

- Boston Bruins

- Buffalo Sabres

- Calgary Flames

- Carolina Hurricanes

- Chicago Blackhawks

- Colorado Avalanche

- Columbus Blue Jackets

- Dallas Stars

- Detroit Red Wings

- Edmonton Oilers

- Florida Panthers

- Los Angeles Kings

- Minnesota Wild

- Montreal Canadiens

- Nashville Predators

- New Jersey Devils

- New York Islanders

- New York Rangers

- Ottawa Senators

- Philadelphia Flyers

- Pittsburgh Penguins

- San Jose Sharks

- Seattle Kraken

- St. Louis Blues

- Tampa Bay Lightning

- Toronto Maple Leafs

- Vancouver Canucks

- Vegas Golden Knights

- Washington Capitals

- Winnipeg Jets

- NCAAF

- NCAAM

- Boxing

- Entertainment

- Lifestyle

- Golf

- MMA

- Soccer

- Tennis

- Wrestling

- More Sports

- RESOURCES

- My Account

- YB on Facebook

- YB on Twitter

- YB on Flipboard

- Contact Us

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

If Michael Jordan isn't the most famous athlete in history, he's certainly on a short list with about two or three others. Certainly, no athlete has had a greater impact on how sports stars are marketed than Jordan. Here's a look at his career, from high school to the pros.

A lifetime of motivation

As a sophomore, Jordan didn't make varsity at Laney High team in Wilmington, North Carolina. He took that hard, and the incident clearly lit a competitive fire that burned so intensely that it bordered on pathological at times.

North Carolina and national attention

After starring for Laney's varsity as a junior and senior, Jordan went on to the University of North Carolina, where he played for the legendary Dean Smith. He was an immediate success. As a freshman in 1982, his jumper in the waning seconds propelled the Tar Heels over Georgetown for the national title and put Jordan on the fast track to stardom. After two more spectacular seasons in Chapel Hill, the NBA beckoned.

Olympic gold in college

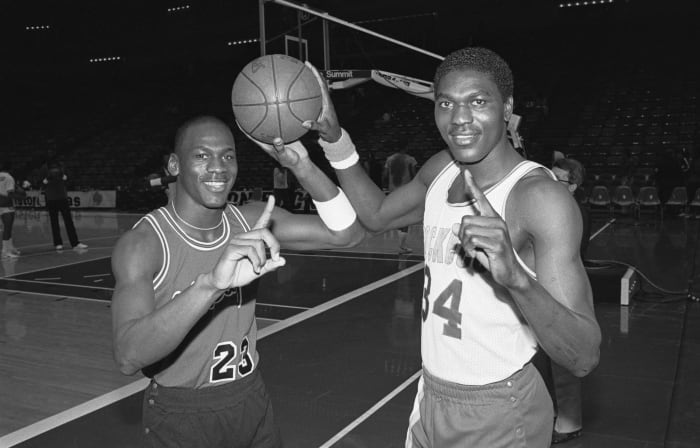

Jordan's first foray into Olympic competition came in 1984 when he played for the United States under legendary coach Bob Knight. On a team that included future NBA stars Patrick Ewing and Chris Mullin, Jordan averaged 17.1 points to lead the U.S. team, which won all eight of its games by double digits on the way to a gold medal.

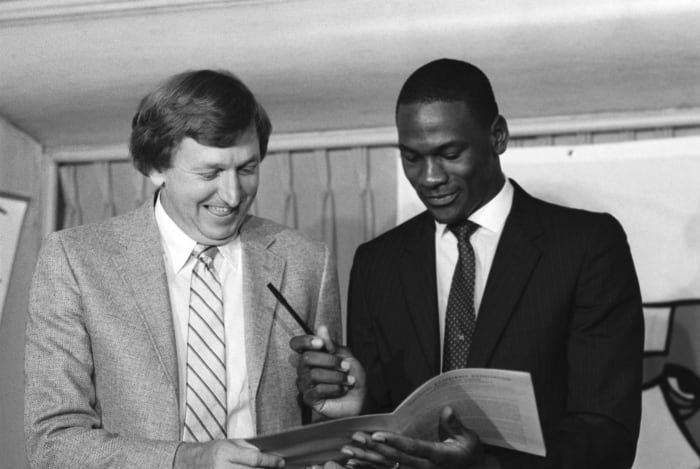

1984 NBA Draft: Bowie over Jordan

It is remembered as arguably the worst, or at least most unfortunate, draft pick not just in NBA history but also perhaps in all of sports history as well. After Hakeem Olajuwon went first to the Houston Rockets, the Portland Trail Blazers selected Kentucky's Sam Bowie despite Bowie already having a significant injury history. Portland's logic was that it already had Clyde Drexler, whose skill set was similar to Jordan's. The Bulls took him with the third pick, and the rest is history.

Rookie of the Year

In 1985, Jordan was named NBA Rookie of the Year after averaging 28.2 points. The Bulls made the playoffs despite a losing record (38-44), but Chicago was bounced by Milwaukee in the first round.

Air Jordans and the birth of a cultural phenomenon

If you had said the words "Air Jordan" to someone in 1983, that person would have looked at you like you were crazy. That changed in 1984 when Nike produced the first edition of what would become the most iconic athletic shoe of all time. The original Air Jordans were outlawed by NBA commissioner David Stern because they violated the league's rule that mandated shoes have a significant amount of white in the color scheme.

Legendary in defeat

Jordan's second season was mostly lost to injury after he suffered a broken foot in the third game. However, he returned in time for the later stages of the regular season, and the Bulls somehow made the playoffs despite a 30-52 record. Chicago's reward was a first-round series against the Celtics, one of the best teams in league history. Although the Bulls were swept, 3-0, Jordan still made his mark, scoring an NBA playoff-record 63 points in Game 2.

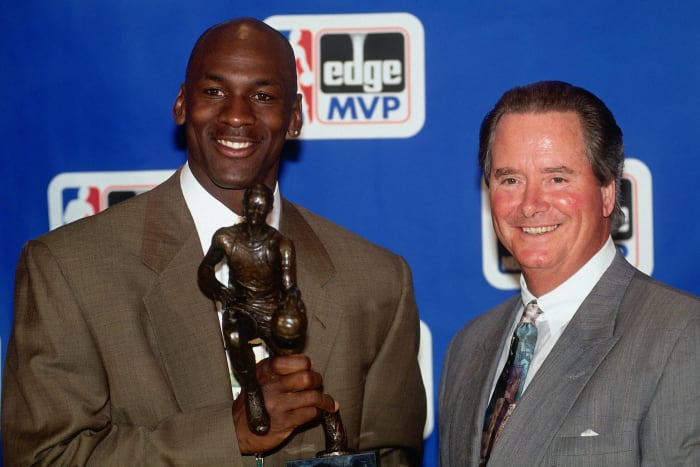

Dominant scorer and MVP

Jordan's third season (1986-87) was spectacular, as he averaged 37.1 points and became only the second player, along with Wilt Chamberlain, to score 3,000 points in a season. He lost out on the MVP to Magic Johnson but won it the next season when he averaged 35 points. His third season began a run in which he would win the scoring title in every full season he played up until his second retirement in 1998.

"The Shot"

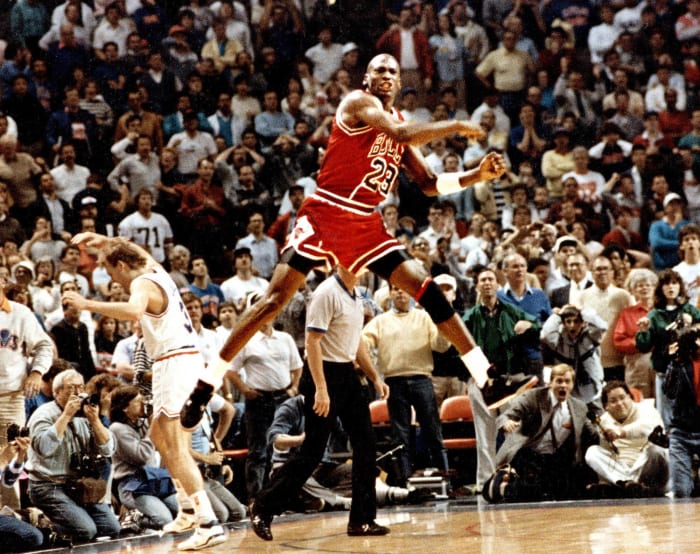

Jordan's reputation as the ultimate clutch player began in Cleveland in 1989. The Bulls trailed the favored Cavaliers, 100-99, courtesy of a Craig Ehlo layup with three seconds left. On the ensuing inbounds play, Jordan beat a double team to get the ball, moved to his left and then hit a double-clutch foul line jumper, besting tight defense from Ehlo, to give the Bulls a 101-100 win and the first-round playoff series..

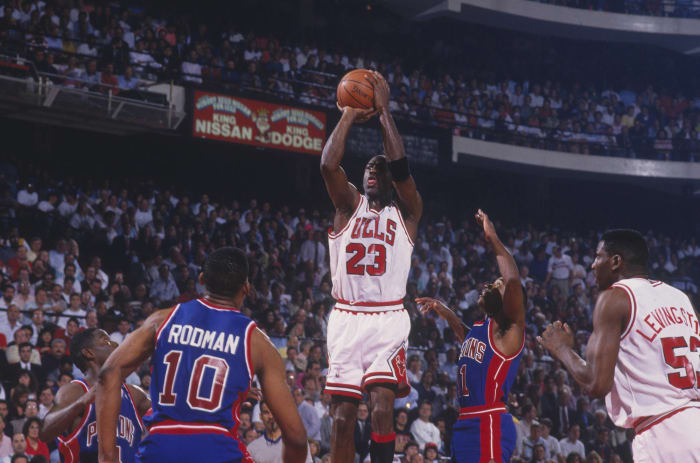

The Pistons and the "Jordan Rules"

Despite Jordan's individual brilliance, the Bulls repeatedly found themselves stymied by a tough, talented "Bad Boys" Pistons teams in the playoffs. Detroit's "Jordan Rules" limited Jordan's freedom on offense, and the Pistons eliminated the Bulls in the second round of the 1988 playoffs and in the 1989 and 1990 Eastern Conference Finals.

Getting past the Pistons

Jordan and the Bulls finally got past the Pistons in the 1991 Eastern Conference Finals, sweeping Detroit and getting revenge for three straight postseason exits. Chicago used the triangle offense, the brainchild of assistant coach Tex Winter and head coach Phil Jackson, and finally handled Detroit's physical — bordering on dirty — defensive style.

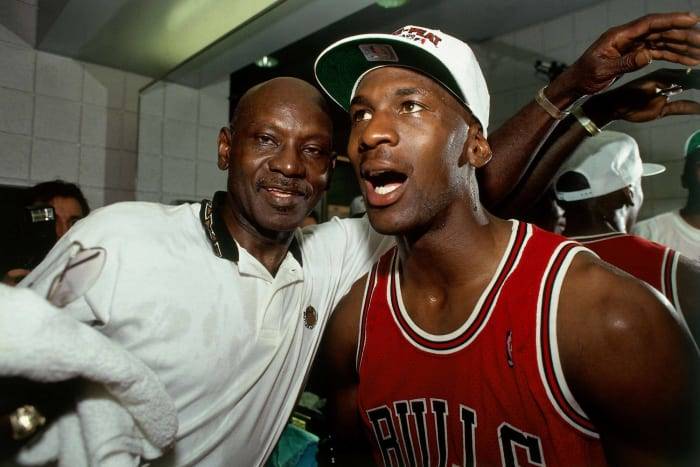

At last a championship

After emphatically defeating their nemesis in the 1991 Eastern Finals, the Bulls met the Los Angeles Lakers in the NBA Finals. The Lakers were no match for a balanced Bulls team, led by Jordan, and Chicago prevailed in five games. MJ averaged 31.2 points and earned the first of six Finals MVP Awards.

The Dream Team

Fresh off a second straight NBA title in 1992, Jordan added to his trophy case later that summer, as he averaged 14.9 points for a star-studded U.S. Olympic squad dubbed "The Dream Team." That squad obliterated the competition on its way to a gold medal, and Jordan was the only player to start all eight games. He didn't have to do much work, though, because most of the games were over after the first 10 minutes.

Three-peat, Part 1

Jordan lost out on the 1992-93 NBA MVP Award to Charles Barkley. He got the last laugh, however, when his Bulls beat Barkley's Suns in six games to win their third straight championship. Jordan averaged 41 points in the series, a Finals record, and became the first player in history to win three straight Finals MVP Awards.

Battles with the Knicks

After leaving the Pistons in the dust, Jordan needed a new foil, and he found one in the rough-and-tumble Knicks, who were led by Jordan's one-time college adversary, Patrick Ewing. The Knicks never got past Jordan and the Bulls in the playoffs, but their battles, which featured plenty of bad blood and interaction between Jordan and the Madison Square Garden crowd (Spike Lee!) were appointment viewing in the early '90s.

Family tragedy

Jordan was on top of the basketball world after three straight titles, but he was rocked when his father, James, was carjacked and killed in July 1993. MJ shocked the sports world with what he did next.

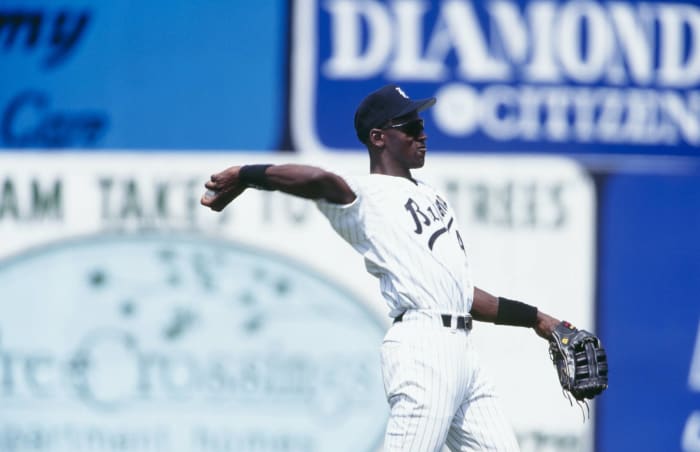

Stepping away ... for baseball?

After his father's death, Jordan retired from basketball in October 1993, citing a loss of desire to play the game. (He alluded to his father's death as a contributing factor too.) He further shocked observers by signing a minor league contract with the Chicago White Sox in February 1994, later stating that the decision was made in part to pursue his late father's dream that he would play professional baseball.

"I'm back."

Although he was starting to have success with the Double-A Birmingham Barons, Jordan quit baseball because of the ongoing Major League Baseball strike and other factors. On March 18, 1995, after some speculation, Jordan announced that he was returning to the hardwood. The news release was brief: "I'm back."

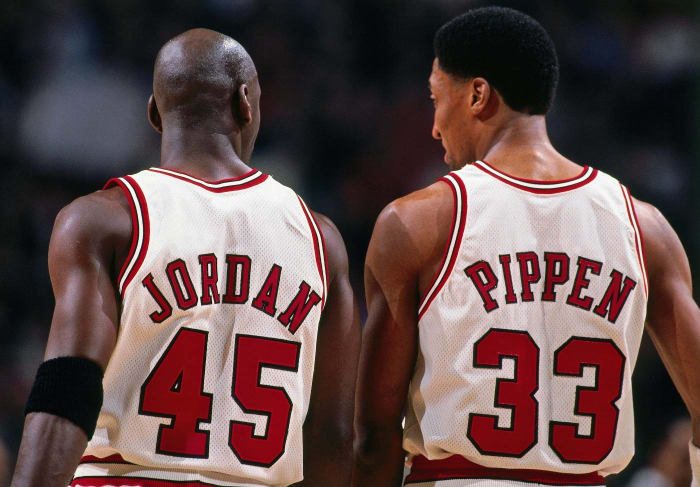

At guard, No. 45, Michael Jordan

Jordan's No. 23, which he had worn since high school, had been retired by the Bulls the previous November. He decided to keep one connection to his brief flirtation with baseball by wearing the No. 45 for Chicago, the same number he had worn with the Barons.

"Double nickel" at the Garden

On March 28, 1995, against the Knicks at Madison Square Garden, Jordan exploded for 55 points in a game that became known as "Double Nickel." The win helped propel the Bulls to a 13-4 mark in their final 17 regular-season games. But Chicago's run at another title fell short — it lost to Orlando in the Eastern Conference semifinals in six games.

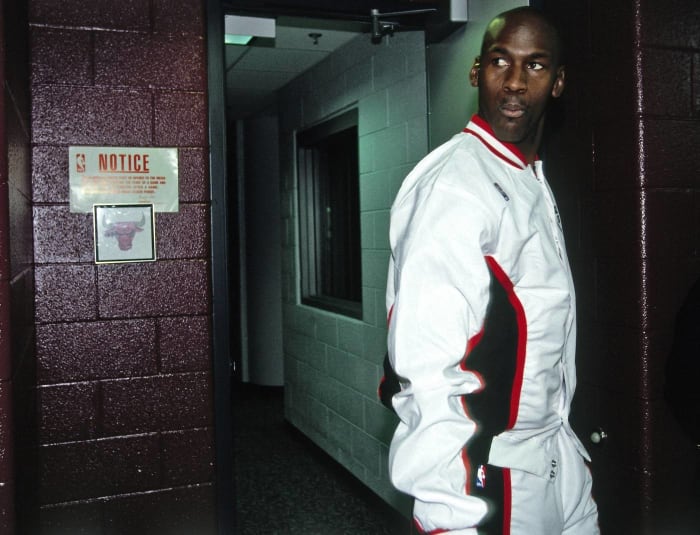

Three-peat, Part 2

Fully back and invested in basketball at the start of the 1995-96 season, Jordan tortured opponents with a new weapon — a virtually unstoppable fadeaway jumper. The Bulls went a then-record 72-10 in his first full season back, and Jordan started a run of three straight scoring titles, three straight championships and three straight Finals MVP Awards. Not bad for a guy who had been consumed by baseball a year prior. In the 1996 Finals. the Bulls beat Seattle in six games.

The "Flu Game"

In the 1997 NBA Finals, the Bulls took on a formidable Jazz team, one that featured league MVP Karl Malone. After hitting a buzzer-beater to win Game 1 for Chicago, Jordan topped himself with his performance in a pivotal Game 5. Weakened by a stomach virus and at times requiring the support of teammates just to stand, Jordan scored 38 points and hit the game-clinching three-pointer with under 30 seconds to go. The performance, viewed by some as the greatest of Jordan's career given his poor health, became known as the "Flu Game."

"The Shot," Part 2

In the 1998 Finals, Jordan's Bulls again met the Jazz, and once again Utah was a tough opponent. Looking to clinch the series in Game 6, Chicago trailed by three with 41 seconds remaining. Jordan hit a jumper to cut the deficit to one and then stripped Karl Malone on the ensuing possession. As he brought the ball down the court, Jordan was isolated on Bryon Russell, faked right, went left (possibly pushing off) and then buried the winning shot with five seconds left.

Retirement again

The Bulls were about to be broken up, with Scottie Pippen, Phil Jackson and Dennis Rodman all on their way out, and the NBA was in the midst of a lockout. So Jordan announced his second retirement, on Jan. 13, 1999. But for Jordan's flirtation with baseball, it's fair to wonder whether the Bulls would have won eight straight championships.

The Wizards years

Jordan moved to the front office in January 2000, as he assumed part ownership of the Washington Wizards. Jordan also took over as president of basketball operations in Washington, a position that afforded him final say over all personnel matters. Unable to stay away from on-court competition and inspired by the NHL comeback of his friend Mario Lemieux, Jordan joined the Wizards as a player at the start of the 2001 season. After two seasons in Washington, Jordan had his farewell tour throughout the latter portion of the 2002-03 campaign.

The final game for real

On April 16, 2003, Jordan played his final game, against the 76ers in Philadelphia. He finished with a pedestrian 15 points on 6-of-15 shooting. After pleas from the crowd and Washington head coach Doug Collins, he reentered the game in the waning minutes and was intentionally fouled by Eric Snow. Jordan hit two free throws, and then the Wizards fouled intentionally so Jordan could check out of the game. As he walked off the court for the final time, Jordan received a standing ovation that lasted several minutes.

More than a man, Jordan the brand

Jordan's exploits on the court made him famous, but he became truly larger than life because of his marketing prowess. He became the first athlete to control his image in terms of advertising and was a recognizable and effective pitchman for a variety of products, including Gatorade, McDonald's and Nike. His Air Jordan shoes were so popular that Nike eventually spun off all things Jordan into a separate brand within the company, known as the Jordan Brand, which uses the "Jumpman" logo.

From player to owner

Jordan bought a minority stake in the Charlotte NBA franchise in 2006 and, as he did with the Wizards, took over basketball operations. In 2010 Jordan became majority owner of the team, the first former player to do so, and the league's only African-American majority owner. Charlotte was 7-59 in the lockout-shortened 2011-12 season — its .106 winning percentage is the worst in league history. The team has had little success in Jordan's reign as owner.

The Last Dance

Jordan's final season with the Chicago Bulls was the subject of a highly-anticipated documentary series that ran on ESPN, and captivated a sports-starved audience during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. The series wasn't necessarily groundbreaking, though it did have its moments, and it put Jordan's name back in the headlines. It also angered some of his former teammates, particularly Horace Grant, but the net effect of the whole thing was to once again make Jordan the focal point of the sports world.

From the court to the race track

Jordan the NASCAR owner might seem like a strange thing to say or type, but he has long been interested in the sport, dating back to his childhood, and then his time spent as a teammate of known racing fanatic Brad Daugherty. Jordan and driver Denny Hamlin announced their partnership and intention to form a team in September, and Bubba Wallace will be their driver, which means that the only Black driver at NASCAR's top level will be paired with a Black majority owner. Jordan made it clear that NASCAR's commitment to racial equality in the wake of racially charged incidents involving Wallace created a situation where he felt that the timing was right for him to jump into the sport in a major way.

Chris Mueller is the co-host of The PM Team with Poni & Mueller on Pittsburgh's 93.7 The Fan, Monday-Friday from 2-6 p.m. ET. Owner of a dog with a Napoleon complex, consumer of beer, cooker of chili, closet Cleveland Browns fan. On Twitter at @ChrisMuellerPGH – please laugh.

More must-reads:

- Hang time: Check out 23 epic Michael Jordan dunks

- 23 memorable events from Michael Jordan's career

- The 'Leading scorers from the 1992-93 NBA season' quiz

Breaking News

Customize Your Newsletter

+

+

Get the latest news and rumors, customized to your favorite sports and teams. Emailed daily. Always free!

Use of this website (including any and all parts and

components) constitutes your acceptance of these

Terms of Service and Privacy Policy.